What did we learn from the Exxon Valdez?

The Exxon Valdez oil tanker struck Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound on March 24, 1989, spilling over 11 million gallons of crude oil in the pristine waters of a remote, rugged Alaska coastline rich with wildlife and thriving communities.

Concerns over the industry’s prevention and response capabilities in Alaska went unaddressed for years. A state agency even justified its approval of an untested industry contingency response plan by describing a large oil spill as “highly unlikely.”

“Highly unlikely” turned into catastrophe

The “highly unlikely” happened. It decimated salmon fisheries. It killed hundreds of harbor seals and thousands of sea otters. It wiped out hundreds of thousands of sea birds, and billions of salmon and herring eggs.

The “highly unlikely” devastated 28 types of animals, from mussels and clams to salmon, bald eagles, cormorants, and killer whales.

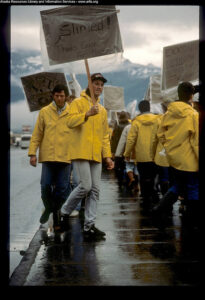

It destroyed the livelihoods and lives of Alaskans, causing financial devastation, the loss of food sources, broken families, and health concerns ranging from lung and skin irritation to post-traumatic stress injury.

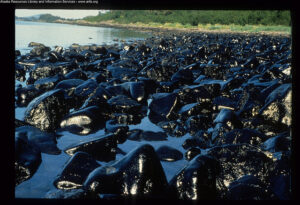

To this day, iconic photos of oil-soaked birds tell the story of industry hubris and greed, and the willingness to put profit over living things.

Oil lurks under the rocks and sand 28 years later

Oil still lurks under the rocks and sand of Prince William Sound beaches because the industry’s “world class” cleanup methods failed. In fact, a 2016 article in Smithsonian.com wonders why we even pretend to clean up oil spills.

The article notes that the oil and gas industry has touted four basic ways to deal with ocean spills since the 1970s—booms, skimmers, fire, and chemical dispersants. “For small spills these technologies can sometimes make a difference,” it continues, ”but only in sheltered waters. None has ever been effective in containing large spills.”

The industry markets technology as the answer, but conventional containment booms don’t work in icy or rough waters. Chemicals and mechanical methods kill oil-eating bacteria and harm rather than help clean up efforts. The money, labor and methods used to clean spills do little to get rid of most of the oil.

The spill’s impact endures in Prince William Sound

What we have learned from the Exxon Valdez oil spill, and thousands of spills since, is that prevention and response programs do not protect us. Spills are not “risks” as much as the industry’s “cost of doing business”—and ordinary people and communities pay the price.

Oil still seeps up from the ground in Prince William Sound. Though the consequences of the Exxon Valdez spill continue to affect Alaska communities and wildlife, the State of Alaska and U.S. Department of Justice dropped a “reopener” claim for $92 million in restoration projects in 2015. The claim amount represents a drop in the bucket of Exxon profits, but our leaders failed to hold Exxon accountable.

Oil still seeps up from the ground in Prince William Sound. Though the consequences of the Exxon Valdez spill continue to affect Alaska communities and wildlife, the State of Alaska and U.S. Department of Justice dropped a “reopener” claim for $92 million in restoration projects in 2015. The claim amount represents a drop in the bucket of Exxon profits, but our leaders failed to hold Exxon accountable.

The oil industry will cuts corners and talk down the risks

Truth is, the oil industry skirted its responsibility to Alaska long before the Exxon Valdez grounded on that reef. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) presented a clear analysis of events leading up to the tanker’s grounding on the 25th anniversary of the spill. It highlights the shortcuts made and concerns dismissed before the then-largest oil spill in U.S. history. (The Deepwater Horizon blowout now holds this dubious distinction.)

- In 1981, the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company disbanded its full-time oil spill team, despite objections from the State of Alaska.

- In 1984, field officers from the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) wrote a detailed memo noting that Alyeska’s pollution abatement equipment had been dismantled and that the company did not have the ability to handle a big spill.

- Also in 1984, federal and state officials deemed an Alyeska oil spill response drill a failure, and DEC staffers in Valdez wrote another lengthy memo detailing the shortcomings of Alyeska’s spill response program.

Yet in 1987, the same year Captain Joseph Hazelwood became master of the Exxon Valdez and received an Exxon Fleet safety award, the state’s DEC approved Alyeska’s untested contingency plan for handling an oil spill of 8.4 million gallons.

Quoting the memo, “It is highly unlikely that a spill of this magnitude would occur. Catastrophic events of this nature are further reduced because the majority of tankers calling on Port Valdez are of American registry and all of these are piloted by licensed masters or pilots.”

A narrative of power and greed, arrogance and betrayal

The bitter irony of this quote harks back to the roots of Shakespearean tragedy—power and greed, arrogance and betrayal.

Eventually, the State of Alaska sued Exxon and the federal government indicted the company for violating the Clean Water Act. Exxon paid $1 billion in settlements to state and federal governments, and $300 million in voluntary settlements with private parties.

Another lawsuit filed on behalf of more than 32,000 fishermen, Native Alaskans, and Alaska landowners resulted in an award of $5 billion in punitive damages, but the Supreme Court reduced that amount to $500 million in 2008. Many Alaskans received pennies on the dollar for their losses after a decade of litigation.

Industry’s “cost of doing business” falls on the back of ordinary people

The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the probable causes of the Exxon Valdez grounding included the lack of effective pilot and escort services, and the failure of Exxon Shipping Company to supervise the master, and provide a rested and sufficient first mate and crew.

In other words, these companies were willing to put corporate profits ahead of people and their homes, lands, food sources, and livelihoods.

Our government won’t protect our health and interests

Twenty-eight years later, we face an administration ruled by fossil fuel company executives. They are removing scientific literature from agency websites, repealing rules that hold industry accountable, and reducing the protections that keep Americans safe, healthy, and involved in what happens in their communities.

We cannot look to our current government to carry out its function of protecting us from industries that cut corners and overreach. We cannot look to our leaders to hold those with dirty hands accountable.

We must remember today, on the anniversary of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, that the fossil fuel industry hoists the risks and consequences of its profits—which line the pockets of its CEOs, lobbyists and the politicians they influence—on the shoulders of Americans and their health, livelihoods and communities.

We must remember today, on the anniversary of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, that the fossil fuel industry hoists the risks and consequences of its profits—which line the pockets of its CEOs, lobbyists and the politicians they influence—on the shoulders of Americans and their health, livelihoods and communities.

We must ask ourselves, will we stand up and hold our leaders and industries to account?