30 years ago, a killing oil

Thirty years ago, the “highly unlikely” happened in Prince William Sound. A giant oil spill altered Alaska forever. Here, Trustees for Alaska board members reflect on the Exxon Valdez oil spill 30 years later.

Dr. Todd Radenbaugh: The folly of trying to wash oil out of nature

On March 24, 1989, when the massive single hulled oil tanker Exxon Valdez struck Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound I was just starting my master’s program at Appalachian State University. At first, all I could think of was why Exxon and the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company were insufficient in containing the spill.

Where were the contingency plans?

At this time in my life, Alaska was just a place for stories of nature, prospecting, and adventure. I gleaned this from books and a few tales of a road trip my great uncle took on the Alaska Highway. Then reality hit, and I realized that 10.8 million gallons of crude oil spoiling an ecosystem that I dreamed of visiting would change everything. How things changed – the spill damaged more than 1,300 miles of remote and wild shoreline and estuaries.

Even in my youthful environmental passion, I realized the folly of washing oil out of nature. Humans are proficient at causing oil spills, not cleaning them up.

Only time and ecosystem functions can heal, I have come to realize how little we understand ecosystems. Now we need to stand back and wait for nature do the work, which takes hundreds of years, not spray hoses and bags.

In 2006, the lure of Alaska brought me to work at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Since then, I have come to admire what is left of the primeval ecosystems of Alaska. I also came to realize that the devastating human-caused environmental disasters would still be with us.

Such spills serve only to remind us of how fast our society can damage the ecosystems we have come to depend on – all in search for cheap oil and profits. Alaska is still healthy, but for how long?

I realize the size of my footprint and I try to reduce it, but I still do not feel I do enough as I watch our current state of declining ecosystem health. Our cumulative actions influence nature. That is why I work with the Trustees of Alaska: to help keep Alaska’s ecosystems healthy so that they can keep us healthy.

Michelle Meyer: A feeling of betrayal

My husband and I had just finished a cross-country drive from Anchorage to his (our) next Army assignment in Fort Benning, Georgia. We were unpacking when I turned on the national news to see the horrifying images of the oil slick in Prince William Sound. I felt nauseous like I’d been kicked in the stomach. I called my family to commiserate, rage and grieve. I remember the overwhelming feeling of loss and alarm at what the future might hold. Feeling all of this at the same time, I also bitterly recall how betrayed I felt–by everyone and anyone who said that this could not, would not ever happen. This experience fueled my environmental and political activism and ultimately, my work with Trustees.

Jim Stratton: The oil is still there

I was waking up at home and listening to KSKA when we heard the news. My wife Colleen worked for the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation in oil spill response, so she looked over at me and said, “I gotta go.”

She didn’t come home from Valdez for three months. I visited her once during that time and she took me along during an inspection of beach clean-up work on Smith Island. I got to see firsthand the hot water washing of a beach. She went on to be the state’s deputy on-scene coordinator the following two years of clean-up work, so our household was immersed in the Exxon Valdez for three years.

Last year, I was on Knight Island with Dave Janka on the m/v Auklet and we dug up inter-tidal oil. It is still there.

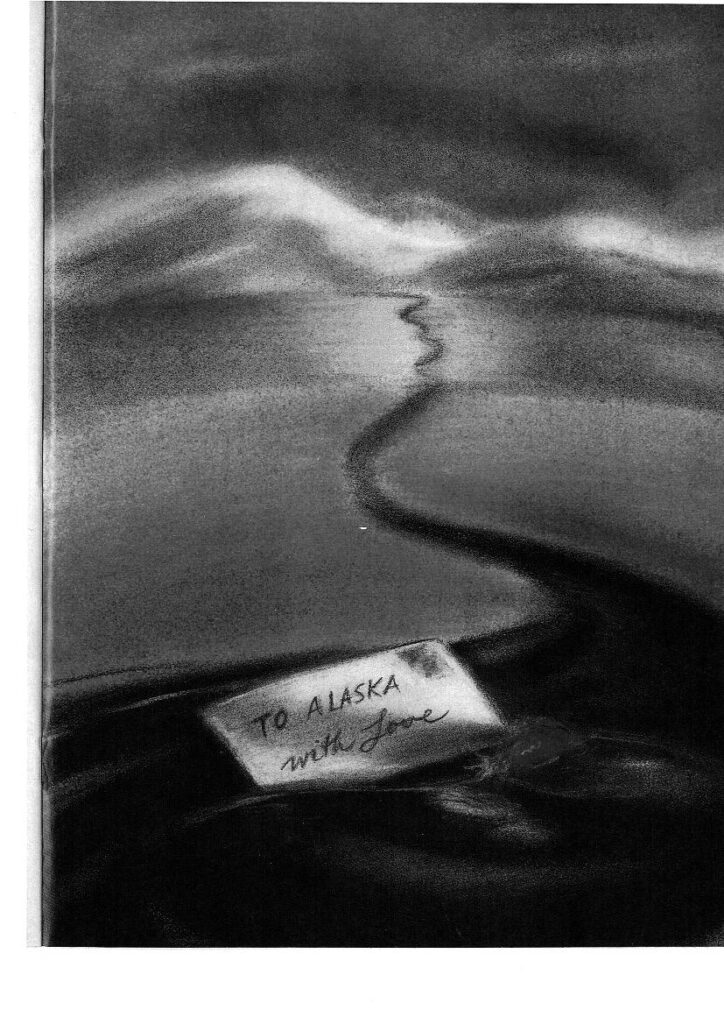

Susan Hackley: To Alaska With Love

I had moved to Boston from Alaska in 1987. When the oil spill happened, an editor for Alaska Magazine asked me to write about it as an expatriate. I had been a former associate editor of the magazine.

This 1989 story expresses the sorrow and outrage I felt. Here’s an excerpt:

The unthinkable had happened. Like the Titanic, the ship that couldn’t be sunk was sunk, or at least had enough holes punched in its hull that its toxic cargo discharged into the sound, poisoning thousands of square miles of pristine ocean. The oil companies that had promised environmentally responsible development of the oil resource had, in fact, proved to be environmentally irresponsible to a murderous degree.

As a result of the spill, bears may die from oil-tainted food. Gray whales slimy with oil have washed up dead on Alaska shores. Otters are dying in anguish of chemical pneumonia, while rescue workers set off firecrackers and other pyrotechnic devices to frighten migratory birds away from polluted beaches.

Peg Tileston: The awful smell

My husband Jules and I had a sailboat in charter with Alaska Sailing Safaris for five years in Prince William Sound. The operators of the charter took many groups around the Sound to introduce them to the majesty of the area. Anchoring in lovely coves, seeing the wildlife and hiking the numerous trails provided their clients an experience they carried with them the rest of their lives.

All that ended when the Exxon Valdez fetched up on Bligh Reef. Cruising in the Sound with lots of oil and dead critters floating around was no longer an appealing vacation option. Our sailboat was no longer in charter.

We did use our boat to join others helping to clean up oiled beaches. Tons of oily debris was stuffed into bags to await pick up and disposal. I can still remember the awful smell and feel of the mess. It was frustrating and disheartening work because we knew that more would come on to the beach with the next high tide.

We still boat in the Sound and continue to find beaches with oil very near the surface. We look in vain for one of the orca pods that disappeared but are pleased to see the otters coming back. Prince William Sound and the surrounding Chugach National Forest is a spectacular area that must be protected.

Although tanker transports are closely monitored, the prospect for another spill is always a possibility.

Tom Meacham: Our worst fears

Present Trustees for Alaska board members Peg Tileston and I were members of the Alaska Water Resources Board, appointed by the Alaska governor, in the late 1980’s. I recall that in late 1988 or early 1989, the board met in Juneau and was given a presentation by either Alyeska Pipeline Service Company or the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (or both), regarding the pipeline safety and spill response plans and procedures for the pipeline itself, as well as at the Valdez Terminal.

After the presentation, I recall board members discussing the presentation among ourselves, led by Dave Vanderbrink of Homer. We reached an informal consensus that the pipeline spill plans appeared adequate. However, we concluded that the Valdez Terminal and tanker plans seemed woefully inadequate and hopelessly optimistic.

No more than a few weeks after that board meeting, our worst fears were realized.